Using an innovative cellular model, the USF Health-led study also discovers drug combinations to prevent degeneration of these tiniest blood vessels

Many diseases arise from abnormalities in our capillaries, tiny exquisitely branching blood vessel networks that play a critical role in tissue health. Researchers have learned a lot about the molecular communication underlying capillary formation and growth, but much less is understood about what causes these critical regulators of normal tissue function to collapse and disappear.

“Capillary regression (loss) is an underappreciated, yet profound, feature of many diseases, especially those affecting organs requiring a lot of oxygen to work properly,” said George E. Davis, MD PhD, a professor in the Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Physiology, University of South Florida Health (USF Health) Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Fla.

Videoclip courtesy of E. George Davis, MD, PhD, USF Health Morsani College of Medicine

“If we know how blood vessels are altered or begin to break down we should be able to fix it pharmacologically,” said Dr. Davis, a member of the USF Health Heart Institute.

A team led by Dr. Davis advanced the understanding of how capillaries regress in a study published Dec. 19 in the American Heart Association journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. The USF Health researchers worked with the laboratory of Courtney Griffin, PhD, at Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

The researchers discovered that three major proinflammatory mediators – interlukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and thrombin – individually and especially when combined, directly drive capillary regression (loss) known to occur in diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and malignant cancer. They also identified combinations of drugs – neutralizing antibodies to specifically block IL-1β and TNFα or combinations of pharmacologic inhibitors – that significantly interfered with capillary regression.

Videoclip courtesy of George E. Davis, MD, PhD, USF Health Morsani College of Medicine

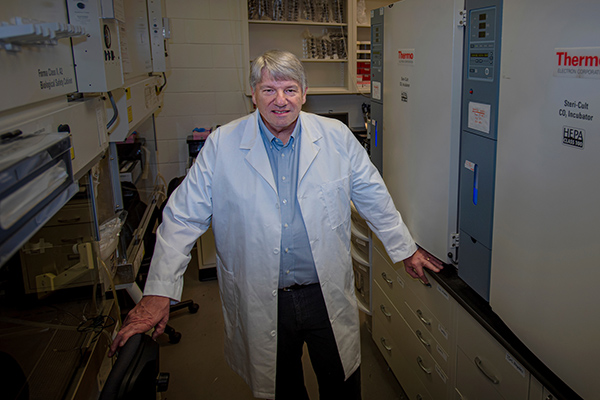

Capillaries, our body’s tiniest and most abundant blood vessels, connect arteries with veins and exchange oxygen, nutrients and waste between the bloodstream and tissues throughout the body. The Davis laboratory grows three-dimensional human “blood vessel networks in a dish” under defined, serum-free conditions to delve into the complexity of how capillaries take shape to sustain healthy tissues. Lately, his team has begun applying what they’ve learned using this innovative in vitro model to attack, and possibly protect against, diseases.

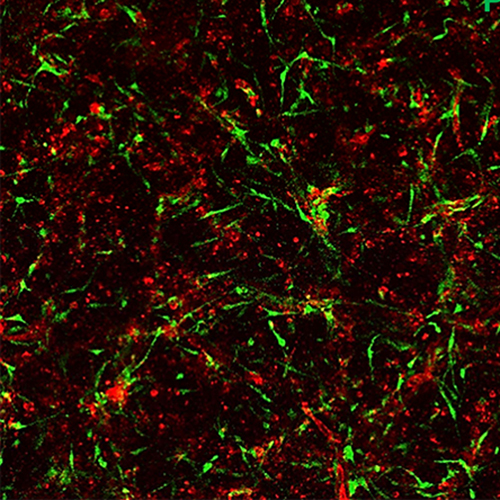

For this study the researchers cultured two types of human cells: endothelial cells, which line the inner surface of capillaries, and pericytes, which are recruited to fortify the outer surface of the endothelial-lined tubes. Cross-communication between these cells controls how the blood vessel networks emerge, branch and stabilize. Macrophages, a type of immune cell, were activated in the cell culture media to simulate a tissue-injury environment highly conducive to capillary regression.

Among the key study findings:

– Macrophage-derived molecules IL-1β and TNFα, combined with thrombin, selectively cause endothelial-lined capillary tube networks to regress; however, pericytes continue to proliferate around the degenerating capillaries. Why the pericytes are spared remains an intriguing question to be answered, but Dr. Davis suggests these more resilient cells may be left behind to help repair tissue damaged by inflammation.

– IL-1β and TNFα, combined with thrombin, induce a unique set of molecular signals contributing to the loss of blood vessels. This “capillary regression signaling signature” is opposite of the physiological pathways previously identified by Dr. Davis and others as characterizing capillary formation and growth.

– Certain drug combinations (two were identified by the researchers) can block the capillary loss promoted by IL-1β, TNFα and thrombin.

USF Health cell biologist George Davis, MD, PhD, grows three-dimensional human “blood vessel networks in a dish” under defined, serum-free conditions to study how capillaries take shape | Photo by Allison Long, USF Health Communications and Marketing

The USF Health researchers found several other proinflammatory molecules that promoted capillary loss, but none proved as powerful as IL-1β, TNFα and thrombin, especially when all three were combined.

Antibodies to counteract the effects of IL-1β and TNFα are already used to treat patients with some inflammatory diseases, including atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease. And physicians prescribe direct thrombin inhibitors for certain patients with atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

“These drugs are out there and they work. Our data suggests that, if combined, they may actually prevent vessel breakdown (earlier in the disease process) and improve outcomes,” Dr. Davis said.

The USF Health team plans to investigate how abnormal capillary response may influence the loss of cells and tissues specific to disease states like sepsis, ischemic heart disease and stroke. Their model of 3D blood vessel networks can also be easily used to screen more potential drug candidates, Dr. Davis said. “We’ve identified some promising (existing) drugs to rescue capillary regression — but there may be more therapeutic opportunities.”

Above: Endothelial cell-lined tubes (red) with associated pericytes (green). Both cell types co-assemble to create the capillary networks vital to the health of tissues throughout the body. Below: Capillary networks following exposure to the three proinflammatory molecules, IL-1 beta, tumor necrosis factor and thrombin, which caused marked loss of the endothelial tubes while sparing pericytes. Images courtesy of George E. Davis, MD, PhD, USF Health.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science & Technology.