Several clinical trials starting at USF Health’s new Heart Institute this year will offer gene and stem cell therapy approaches to healing damaged hearts

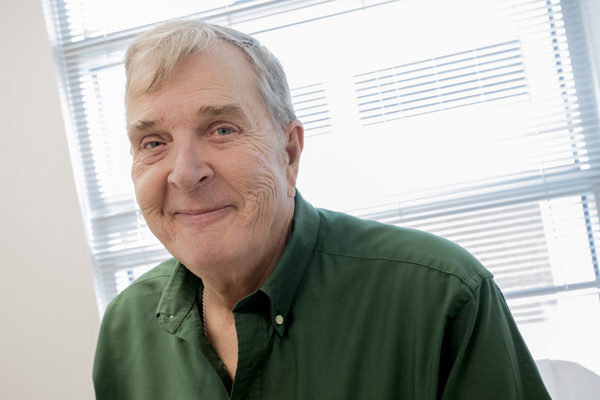

Over the past 18 months, David Skand has been hospitalized four times, twice in intensive care. In June, the 70-year-old Tampa Bay Downs racetrack veterinarian found himself in the hospital once again. This time was different, though. This time he was filled with hope.

Skand is the first of 10 USF Health patients enrolled in a clinical trial for a genetically-engineered drug designed to treat chronic heart failure. The drug, developed in Shanghai, China, signals a patient’s own cells to remodel the heart.

Senior research nurse Bonnie Kirby speaks with trial participant David Skand and USF Health Heart Institute Director Dr. Leslie Miller.

It is the first of several trials getting under way at USF Health’s new Heart Institute. The institute, which was recently awarded $8.9 million in state and county funding, is focused on regenerative medicine using the latest in gene and stem cell therapy, as well as genomics-based personalized medicine.

“This is a significant change in thinking and goals,” says USF Health Cardiovascular Sciences Chair Dr. Leslie Miller, a renowned cardiologist and leading international specialist in heart failure and transplantation who leads the institute. “We are not just helping improve heart function, we are driving the heart’s native repair mechanisms.”USF is one of 10 sites for the randomized, double-blind study—the first test of the drug in the United States. For some patients, the drug, called Neucardin, could mean the difference between a heart transplant and a simple drug infusion.

Of the 120 patients who will eventually be enrolled in the study, 80 will receive the active form of the drug, while 40 will receive a placebo.

Dr. Leslie Miller says it is important for patients, like David Skand, to hear from him, as well as the research coordinator, about the risks and benefits of a trial.

“It’s thrilling,” says Skand, who was diagnosed with chronic heart failure in 1993. “I think this is going to help a lot of people in this country.”

He’s not worried about the possibility of receiving the placebo. “I have a 66 percent chance of getting it,” he says with confidence. “But the point is, you are still getting evaluated by the top doctors and the top nurses and undergoing really tremendous diagnostic procedures every day.”

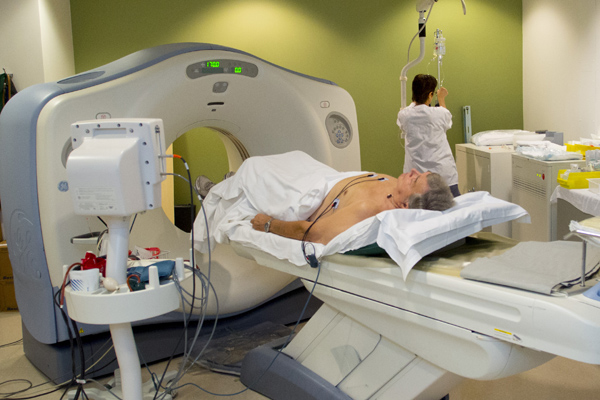

For eight hours a day over 10 days in late June, Skand received either the drug or placebo through a small subcutaneous cathether. Studies to date show minimal side effects from the drug, occasionally a little nausea. Doctors continue to follow Skand closely since he left the hospital after the extended infusion, particularly in the first six months when the greatest change in heart function would likely occur.

“The best would be an improvement in my ejection fraction,” Skand says, referring to the amount of blood his heart pumps out with every beat. “That would make a big difference for me. I’d be less tired; I could do more things, like walking and climbing stairs. And it would help my mental outlook a great deal.”

A radiologist at the institute reads a CT scan of the heart.

The Neucardin trial is the first of five planned trials—three gene therapy trials and two stem cell trials—at the institute this year. The trials are focused on preventing and reversing disease processes. There’s also a major study in partnership with the American College of Cardiology (ACC) to identify genes that are markers of atherosclerosis and other forms of coronary artery disease.

The need for new diagnostic tools, such as the use of genomic markers to detect and predict disease, and new therapies, such as stem cell and gene therapy, is indisputable. In Florida alone, cardiovascular disease accounts for 40 percent of all hospitalization and deaths. Estimates put the state’s costs for cardiovascular care at $17 billion by 2020.

But the problem isn’t isolated to Florida. According to Miller, cardiovascular disease is the biggest health risk in the world.

“The data is unequivocal. One in four people in the U.S. have cardiovascular disease. By 2020, it will be one in three,” he says. “The new Heart Institute is a critical step toward saving lives by finding new diagnostic tools that will allow earlier detection and better prevention, as well as new and improved therapies to improve outcomes.”

Patients enrolled in the Neurocardin trial are closely monitored after leaving the hospital, particularly in the first six months.

The ACC selected the Heart Institute as its partner for the first-ever trial linking genomic screening with its clinical database of patients.

“The ACC has millions of patients enrolled in registries and all the data for every type of cardiovascular disease,” Miller says. That data could help researchers identify individuals at risk for disease, allowing doctors to intervene long before a heart attack.

It could even help identify, early-on, children who may be at risk for developing the same heart condition as their parents.

“We want to do some out-of-the-box thinking about interventional treatments,” Miller says. “We might be able to introduce a statin at an early age to retard the development of atherosclerosis.”

Genetic markers have already been used in other fields to predict the likelihood of disease and introduce interventional treatments.

Cancer researchers, for example, have found that a significant percentage of women with breast cancer carry the genetic marker BR2a. The correlation is so strong, Miller says, that an increasing number of women who carry the gene are choosing to undergo a double mastectomy to prevent or reduce their risk for the disease.

Along with understanding risk, genetic discoveries could help doctors identify which treatments are most effective for individual patients as well as provide insight on appropriate dosing.

The gene and stem cell therapy trials offered by the institute will focus on preventing and reversing cardiovascular disease processes.

It’s the future of cardiovascular care and it places USF at the center of some of the most advanced research in the world, which is attracting leading scientists.

In March, Dr. Jennifer Hall, a nationally prominent cardiovascular genomics researcher joined the institute in March. Her work in translational genomics—using a patient’s own genetic code to guide medical care—will be key to the ACC study.

But, USF Health’s focus on personalized medicine isn’t limited to heart disease. In June, Dr. Stephen Liggett, a nationally prominent researcher in genomics-based personalized medicine, joined USF Health as associate vice president of personalized medicine and director of the Center for Personalized Medicine and Genomics. Liggett’s initial collaborations will include Miller’s work at the Heart Institute.

“This field is moving so rapidly,” says Miller, calling this the most exciting time of his career. “A tube of blood allows us to have your whole DNA analyzed—a huge array of data to put in usable form for doctors to take care of patients.”

Skand, a racetrack veterinarian, says the new drug could make a big difference, enabling him to do more things and improving his outlook on life.

It’s the kind of research that could revolutionize healthcare, according to Dr. Stephen K. Klasko, CEO of USF Health and dean of the Morsani College of Medicine.

“We believe that the technology developed here will herald a new day and that USF Health will be able to partner with the best industry and academic partners throughout the world to develop these new personalized and genetic approaches to health.”

Postscript: Dr. Skand notes he has felt much better in the initial months following the drug infusion, but neither he nor the healthcare practitioners involved in the blinded clinical trial will know whether he received active drug for likely a year.

Story by Ann Carney/Reprinted from USF Magazine, Fall 2012

Photos by Eric Younghans, USF Health Communications