As the anesthesia took full effect, Freud dozed on the surgical table at the USF Health Center for Advanced Medical Learning and Simulation.

The juvenile green sea turtle was oblivious to the crowd of reporters and photographers recording every move of The Florida Aquarium and CAMLS team preparing the docile creature for a series of advanced imaging tests to help diagnose a suspected tear in the lung.

Veterinarian Kathy Heym, DVM, had reached out last month to CAMLS, The Florida Aquarium’s downtown neighbor, for assistance in finding the source of injury, or leak, causing the body cavity outside the turtle’s lungs to abnormally fill with air. All that trapped air creates undue pressure on the turtle’s shell and organs, creating a potentially life-threatening condition as he matures. It also means Freud floats a lot, so he cannot swim long enough at depths or dive down for meals of sea grasses; the aquarium staff serves him food on a pole. In the wild, a super-buoyant turtle would likely soon be an easy target for predators.

“Working with the CAMLS team to go the extra mile for this animal has been phenomenal,” Dr. Heym said. “They’ve provided us access to imaging technology and special instruments that we would not usually have access to. It’s great to have this type of support in our own backyard.”

“CAMLS is the world’s largest simulation and training center with cutting-edge technology. We’re also a good neighbor,” said USF Health trauma surgeon Luis Llerena, MD, medical director of CAMLS Surgical Intervention and Training Center. “So, when The Florida Aquarium came to us, we said we’d love to help.”

Getting their first look at the sea turtle, Tampa Bay area media surround Freud, who was brought into the CAMLS Surgical and Interventional Training Center in a small crate.

At 22 pounds, Freud is estimated to be age 10 to 15; sea turtles can grow to over 300 pounds and live 80 to 100 years. Though referred to as “he,” the young sea turtle’s sex is undetermined because he hasn’t reached the age of sexual maturity.

Freud was stranded on a beach in the Florida Panhandle in November 2012. The listless sea turtle was covered with algae and bloated when rescued and brought to Gulf World Marine Park in Panama City Beach for rehabilitation. He was transferred to The Florida Aquarium, the Tampa Bay area’s largest aquarium, in January 2013.

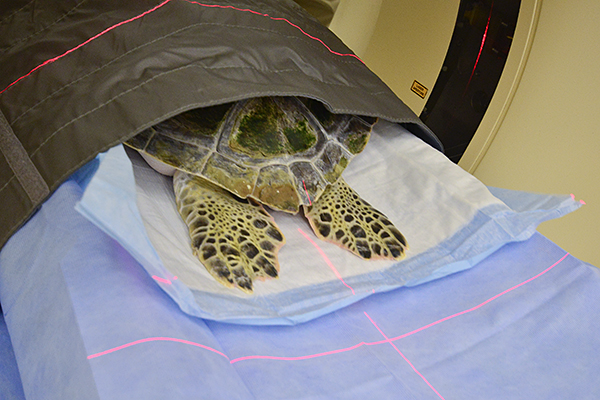

Before arriving at CAMLS for advanced diagnostic testing, Freud underwent a couple of inconclusive computed tomography (CT) scans and a laparoscopic procedure, without success in pinpointing the potential hole or holes leaking air from his lungs.

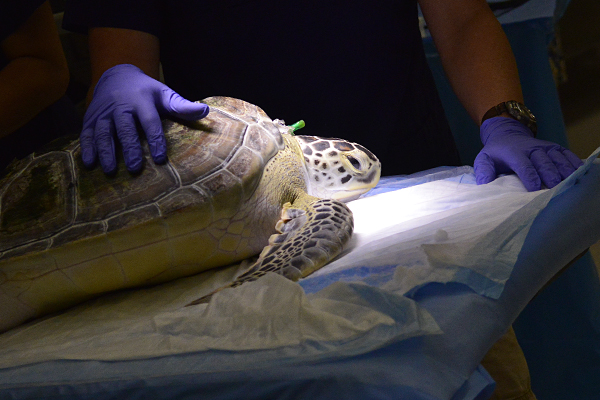

Susan Coy (left), veterinary technician for The Florida Aquarium, preps sea turtle Freud for the series of CT-scans, which were performed by Summer Decker, PhD, director of research imaging at USF Health Radiology.

Kathy Heym, DVM, veterinarian at The Florida Aquarium, speaks with USF Health trauma surgeon Luis Llerena, MD, medical director of the CAMLS Surgical and Interventional Training Center.

The Dec. 10 visit to the university’s simulation center involved two procedures.

First, Freud underwent a series of CT-scans enhanced for clarity and maximum detail by USF Health researchers with expertise in three-dimensional imaging and pre-operative planning. Summer Decker, PhD, director of imaging research at the Morsani College of Medicine’s Department of Radiology, said the scans she captured would be shared electronically with Todd Hazelton, MD, USF Health chair of radiology, and colleagues at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center and Marathon Veterinary Hospital in the Florida Keys so they could offer additional insight.

Secondly, while in sum the three CT-scans indicated that Freud’s lungs appeared healthy, the team decided to perform a bronchoscopy to try to localize the site of the leaking air. Dr. Llerena inserted the thin fiberoptic scope with miniature camera attached down the sedated turtle’s windpipe to view inside the airways.

“On a turtle what’s a normal CO-2 (carbon dioxide) reading?” Dr. Llerena turned to ask Dr. Heym, who helped guide him through the process carefully monitored by the The Florida Aquarium’s veterinary team. “This is really different than a human.”

Assisted by the veterinary team, Dr. Llerena prepares to insert the specialized bronchoscope into the sedated turtle’s windpipe to get a view inside the animal’s airways.

As Dr. Llerena carefully manipulates the high-tech scope through Freud’s airway, a real-time view appears on the monitor above.

The bronchoscopy showed air bubbles where smooth tissue should be at the left-side base of Freud’s lung. Dr. Llerena was able to pinpoint and record on videotape for further review the location of the bubbles (lesions). The next step, Dr. Heym said, will be to correlate the CAMLS CT-scan findings with the bronchoscopy results. Taking that information, sea turtle veterinary experts could brainstorm with human pulmonologists and surgeons, to figure out if there is a least invasive approach for repairing the potentially life-threatening condition given the anatomical limitations of surgery on a turtle.

CAMLS worked with partners — including STORZ, the medical device company that supplied the specially-sized bronchoscope, and Stryker – to make sure that the high-tech diagnostic evaluation was adapted to meet the needs of the aquarium’s patient. Even the CT-scan radiation dosage protocol was modified to account for the sea turtle’s pediatric size.

“This turtle would have a really difficult time with us finding a solution, if we didn’t have the opportunity here today.” Dr. Heym said, referring to CAMLS donation of staff time, equipment and facility.

Sea turtles play a critical role in the ecological system and health of the earth’s oceans, so teaming up within the community to help save the animals benefits everyone, she added. That’s also why the best-case scenario would be to find a fix for what ails Freud and release him back into Florida waters, close to where he was rescued.

Florida is home to five species of sea turtle and most, including Freud’s green turtle species, are endangered.

“So every turtle counts,” Dr. Heym said. “That’s the ultimate goal with all these guys – to get them into rehab and get them back out there, so they can contribute to (increasing) the population moving forward.”

L to R: The USF Health team — Jonathan Ford, biomedical engineer for the Department of Radiology, Summer Decker, director of research imaging for Radiology; and Dr. Luis Llerena, medical director of CAMLS Surgical and Interventional Training Center; with The Florida Aquarium team — Susan Coy, veterinary tech; John Than, associate curator; and veterinarian Kathy Heym, DVM.

Photos by Eric Younghans, USF Health Communications, and video by Allyn DiVito, USF Health Information Systems