National organization partners with USF Health, Moffitt and community advocates to broaden diversity

Story by Sandra Roa and Anne DeLotto Baier

Jumpstarting the critical work needed to broaden the genetic diversity of clinical trials was the focus when medical professionals and community leaders gathered in Tampa recently.

The safety and effectiveness of new drugs, vaccines, medical technology and other treatments will be optimized only when communities of color are adequately represented in the patient-oriented studies known as clinical trials, the group agreed.

Tampa community leaders met with USF Health and Moffitt researchers to discuss the need for increased minority participation in research trials.

“I have already seen it right here, in the Tampa Bay community, where we have people in the African-American community dying 10 years earlier than their Caucasian peers,” said Kevin Sneed, PharmD, dean of the USF College of Pharmacy.

“We need a much broader spectrum of the population to make sure that a medication shown to be effective for one group is actually very effective for all the people who we intend to treat with that medication.”

Dr. Sneed was one of the panelists at the Tampa Bay region’s first Community Advocacy Matchmaking (CAM) luncheon and workshop held April 24. The event was sponsored by 50 Hoops and the National Physician and Family Referral Project in partnership with USF Health and Moffitt Cancer Center.

The CAM group also will lay a foundation for the types of community education and local strategies that will help successfully increase minority enrollment in clinical research.

Kevin Sneed, PharmD, dean of the USF Colllege of Pharmacy, said increasing genetic diversity in clinical trials is critical for developing the most effective medications and other new treatments. He timed his talk with his iPhone.

Tackling the challenge of personalized medicine

Initiatives to include more minorities and women in clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health were mandated with the Revitalization Act of 1993. Yet, while African-Americans, Latinos, Asians and mixed sub-groups comprise almost 40 percent of the U.S. population, current clinical trial demographics do not reflect that same diversity.

In fact, non-whites still account for less than 5 percent of clinical trial participants. And while they bear a disproportionate share of several types of cancers, Latinos and Blacks have a participation rate of less than 2 percent in cancer clinical trials, according to a study published last year in the journal Cancer.

This narrow pool of DNA variants provides a very limited sample for researchers to study as they develop new treatments.

Ed and Patricia Sanders, founders of 50 Hoops, organize workshops nationwide to help communities increase minority recruitment into clinical trials.

Advances in molecular medicine are demonstrating that how a particular prescribed drug works for an individual patient, or subset of patients, is based in part on genetic variations within patient populations. A significant portion of patients don’t have the same reaction to the same drug. Yet, until recently drugs were typically prescribed with a “one size fits all” approach, resulting in trial and error until the optimal drug and dose is found.

The emerging field of pharmacogenomics – studying how an individual’s DNA influences his or her response to drugs — has begun to allow prescribers to individualize therapy. This promises to decrease chances for adverse drug reactions, and improve health outcomes – if the genetic samples that researchers use when testing new medications are large enough to represent lots of variation in genetic patterns.

“We need our DNA in these trials. When my daughter or my grandson are on a surgery table and something is being administered to them, I want to know that at least 10 to 12 percent African-Americans have been tested,” said Patricia Sanders, director of the 50 Hoops/NPFR project.

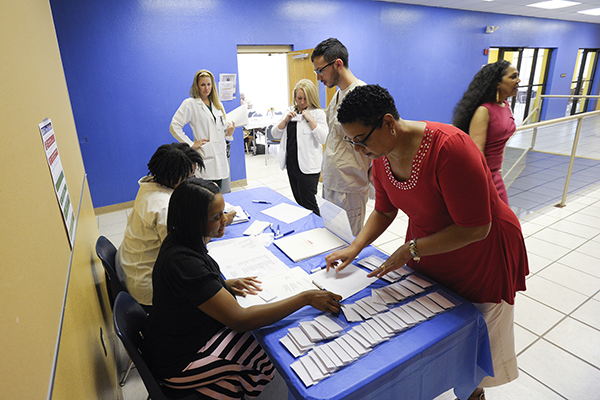

Many medical professionals and community leaders registered to attend Tampa’s first Community Advocacy Matchmaking workshop.

Building trust with advocates in minority communities

Sanders works at the grassroots level connecting doctors, nurses and other clinical research professionals with community stakeholders to promote meaningful representation of African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos and other underrepresented populations in clinical trials.

At the Tampa CAM event, participants – including key leaders from local African American and Hispanic/Latino communities — discussed some of the barriers to clinical trial access and participation. They touched on everything from lack of transportation, cultural factors and concerns over undocumented status to mistrust of doctors outside the community.

“One way to move towards a trusting community is to make sure that some of the researchers look like me,” said Walter Niles, MPA, manager of the Office of Health Equity at the Hillsborough County Health Department. “Looking across the spectrum of the research team, (a potential clinical trial participant) ought to see some indications of diversity.”

Walter Niles, MPA, manager of the Office of Health Equity at the Hillsborough County Health Department spoke about ways to help increase racial and ethic diversity in patient-oriented studies.

The advocacy workshop emphasized the importance of building enduring relationships in communities so that people feel empowered to engage in studies that may lead to better treatments for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, certain cancers and other conditions that disproportionately affect minorities.

Connecting those underrepresented in clinical trials to the research critical to their health or the health of their descendants requires a dedicated, ongoing effort, Dr. Sneed said.

“We’ve begun the conversation,” he said. “As researchers interested in evidence-based care we must continue to answer questions with transparency, to build trust with advocates in the Tampa Bay community, and, hopefully, increase minority participation in clinical research.”

Each Community Advocacy Matchmaking workshop participant received resources needed to contact local community leaders and medical professionals to help with recruitment of minority communities.

Worshop participants discussed some of the barriers to clinical trial access and participation — everything from lack of transportation, cultural factors and concerns over undocumented status to mistrust of doctors outside the community.

Counterclockwise from far left: Pat and Ed Sanders, Hiram Green, Walter Niles, Chuck Wilson, Evangeline Best, Rosa Mckinzy Cambridge, and Amparo Nuñez were panelists at the Community Advocacy Matchmaking workshop.

Video by Sandra Roa and photos by Eric Younghans, USF Health Communications and Marketing