The diagnostic blood test being developed is intended to speed treatment critical to improving ischemic stroke outcomes

Stroke survivor Lauren Barnathan was one of the first patients to donate a blood sample for the pilot study of a stroke diagnostic test under development by VuEssence Inc and USF Health Neurology.

Lauren Barnathan, who routinely works with stroke patients as a speech pathologist at Tampa General Hospital, is athletic, maintains a healthy diet, and meditates.

And in January 2018, at age 30, she suffered a life-threatening stroke. A tear in the right carotid artery in her neck led to blood clot that dislodged, blocking blood flow to part of her brain.

Barnathan was among the first patients to donate a blood sample for a pilot-feasibility study teaming USF Health Neurology with VuEssence Inc., a Tampa Bay area medical device company with a laboratory based in the USF Research Park. The ongoing study aims to develop a blood test that can accurately and rapidly detect when a person is having an acute ischemic stroke based on measurable biomarkers in the blood – and, ultimately, help guide treatment decisions for better outcomes.

“On the night of my stroke, when they were consenting me to be part of the study in the emergency department, I remember thinking how great it would be to have a test like that,” said Barnathan, whose fiancé Adam Barnathan, an ER medicine physician (now her husband), called 911 as soon he saw symptoms: facial droop and an inability to use one side of her body. Her timely and successful treatment at the TGH Comprehensive Stroke Center included the blood clot-dissolving drug tPA and a minimally-invasive procedure (mechanical thrombectomy) to physically retrieve a clot from the vessel blocked in her brain.

W. Scott Burgin, MD, professor and division chief of vascular neurology at USF Health Morsani College of Medicine, leads the Comprehensive Stroke Center based at Tampa General Hospital.

A potential “game changer” for stroke neurology

No reliable early-detection test exists to identify a stroke – the fifth most common cause of death and the leading cause of long-term disability in the U.S. Most strokes are ischemic, meaning that blood flow to the brain is obstructed by a clot in an artery. Once deprived of oxygen-rich blood, brain cells begin dying. And, stroke outcomes – including recovering the ability to walk, speak, see, understand, reason and/or remember — are generally worse the longer treatment is delayed.

“When I look at all the things that could change the way I’ve practiced stroke neurology all these years, this new diagnostic test would be one of the biggest game changers,” said W. Scott Burgin, MD, professor and division chief of vascular neurology at USF Health and director of its Comprehensive Stroke Center based at TGH.

A one-hour delay in treating stroke equals more than 450 miles of nerves cells, the approximate distance from Tampa to Atlanta, Dr. Burgin said. “And that’s a lot of brain tissue lost. So, any technology that can improve our ability to diagnose accurately and quickly would likely translate into a huge improvement in patients’ functional outcomes.”

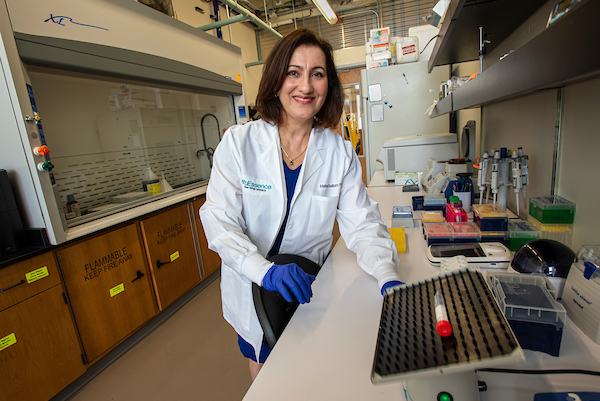

USF engineering alumna Maha Sallam, PhD, is president and founder of VuEssence Inc., a Tampa Bay medical device company

Dr. Burgin (a clinical advisor to VuEssence) has been consulting with Maha Sallam, PhD, president and founder of VuEssence, on development of the early-detection stroke test. This applied research project between the university and industry partner VuEssence is funded in part by a Florida High-Tech Corridor Matching Grant, which supports stroke investigator efforts, scientific input into trial design and administration, and study logistics.

So far, about 200 blood samples have been collected for analysis from consenting patients who arrive at TGH’s emergency department with a suspected stroke, and the researchers plan to collect 200 more.

Doctors currently use clinical assessment, including a physical examination and obtaining a medical history, and brain imaging with MRIs and CT scans to assist with stroke diagnosis. Combined with ambulance transport to the hospital ER, these standard diagnostic methods can take hours, increasing the risk of serious brain injury.

“Getting someone treated within a short time period can be complex.” Dr. Burgin said.

Adding stroke-specific gene expression to diagnostic arsenal

Other diseases, such as low or high blood sugar, epilepsy, or migraines affecting one side of the head, can mimic stroke – and may need to be ruled out before specialized treatment by a multidisciplinary stroke team begins. And in the earliest stages of stroke, Dr. Burgin said, CT scans of the brain often appear essentially normal.

Blood samples are analyzed for stroke-specific gene expression at the VuEssence laboratory in USF’s Research Park.

“Right now, physicians really don’t know how the underlying biology in the body, the gene expression, is changing for a particular patient exhibiting acute stroke symptoms,” said Sallam, a USF graduate with a doctorate in computer engineering. “We hope to add that avenue of new information to existing diagnostic tools.”

VuEssence scientists analyze blood samples for specific products made by genes (gene expression) in response to the trauma happening in cells during stroke onset. Such genetic information may help doctors detect a stroke versus a condition that mimics stroke. The technology may also help differentiate the type of ischemic stroke – for example, indicate high probability of emergent large vessel occlusion that could benefit from a mechanical thrombectomy to remove the clot.

The company continues to reduce the time required to identify stroke-specific gene expression in the blood, with promising preliminary results, Sallam said. “Our goal is to get the system to process the patient’s blood (for stroke detection), so that critical test results are available less than 15 minutes” from the time blood is drawn.

To speed stroke treatment, diagnostic test results need to be available soon after a patient arrives at the hospital – if possible, even before.

Blood is collected from consenting patients who arrive at Tampa General’s emergency department with symptoms indicating high likelihood of stroke.

Long-term goal: Portable test device on ambulances

Both Sallam and Dr. Burgin agree that, ideally, the diagnostic blood test would be incorporated into an easy-to-use, portable device that paramedics and other first-responders could carry for pre-hospital detection and differentiation of strokes.

That would provide emergency medical services a much-needed tool to identify individuals with likely severe strokes, so those patients can be directly transported to the closest facility equipped for immediate endovascular therapy, Dr. Burgin said.

“If we get the test to work, the (long-term) goal would be to make it universally available on ambulances, whether in rural Montana or New York City,” he said. “In Montana, getting a patient to a specialized stroke center can be a significant endeavor. But, if the patient’s dizziness is caused by a stroke mimic, such as low blood sugar, they can probably go to the nearest hospital.”

First, though, VuEssense is focused on developing a streamlined test to be FDA approved and implemented in hospital settings and emergency departments, Sallam said. “If all goes well,” she added, “it will take some time before the point-of-care diagnostic technology could be available in ambulances.”

***

This February, Barnathan finished her first half-marathon at the Gasparilla Distance Classic in Tampa.| Photo courtesy of Lauren Barnathan

Barnathan, who overcame mobility and balance challenges after hospitalization, made virtually a full recovery. She returned to work about a month after her stroke, danced at her wedding several months later, and this February ran her first half-marathon, the Gasparilla Distance Classic, with her husband.

But in her professional role she sees stroke survivors who have not been as fortunate.

“Anything that can help expedite the process of intervening to minimize stroke damage would be a huge win,” she said.

Lauren with her husband, Adam Barnathan, MD, an emergency medicine physician| Photo courtesy of Lauren Barnathan

-Photos by Allison Long, USF Health Communications and Marketing