“Memory formation is paramount in making us who we are today,” USF Health neuroscientist Edwin Weeber, PhD, told an audience of hundreds attending the recent TEDx TampaBay 2014 conference at the Tampa Convention Center.

That’s how Weeber, professor and chief scientific officer at the USF Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute, launched his TEDx presentation “What We Know About the Human Brain.” The May 15 talk was part of a series of short, powerful presentations intended to expose attendees to an eclectic mix of innovative ideas.

USF Health neuroscientist Edwin Weeber spoke at TEDx TampaBay 2014.

Weeber leads one of a handful of laboratories nationwide working to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying cognitive disruption in a mouse model for Angelman syndrome, a rare neurogenetic disorder affecting children. He is principal investigator for a recently completed clinical trial testing the effectiveness of the antibiotic minocycline in treating Angelman syndrome.

In his presentation, Weeber recalled the vivid experiences in his own life that helped shape a career focused on the neurobiology of learning and memory.

His beloved grandmother’s slow decline from early signs of memory loss — like burning cookies because she forgot to turn off the oven — to Alzheimer’s disease happened while he was away at college.

“I visited her when I was home from school, and she could not recognize me. That hurt and really affected me,” Weeber said. “Yet, I was struck by how her long-term memories of 50, 60 or 70 years ago remained intact.”

That experience prompted him to change his graduate studies from microbiology to neuroscience. The more he learned about the brain, Weeber said, the more he realized that the brain’s potential to store information may be unlimited, or at least that its capacity is greater than we think. He wondered if it might be possible to recover the processes underlying memory, even for a short time, in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

After receiving his PhD in neuroscience, he joined the laboratory of David Sweatt, PhD, a neuroscientist at Baylor University College of Medicine renowned for his multidisciplinary approach to studying learning and memory. Meanwhile, down the hall from Sweatt’s laboratory, another scientific team identified the single gene defect causing Angelman syndrome and then disrupted that gene in a mouse to create a mouse model of human cognitive disorder.

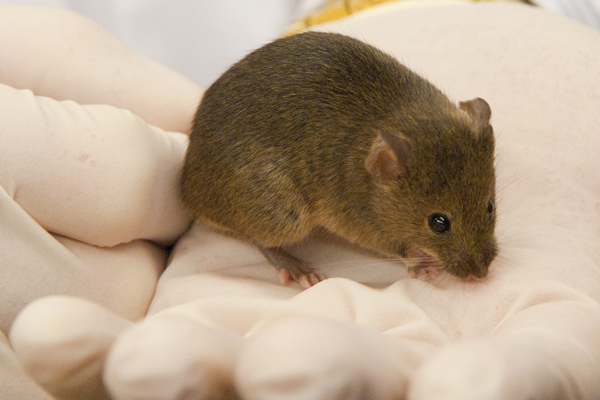

Today, the genetically-altered Angelman syndrome mice mimic the same major symptoms seen in children with the disorder, including problems with memory and balance.

Mice, which share more than 90 percent of the genes found in people, make good models for studying the human brain, Weeber says.

As he worked with the Baylor mice models, Weeber discovered that he could reverse the neurological effects of Angelman syndrome by preventing the inhibition of CaMKII, an enzyme critically involved in the proper functioning of synapses and processes underlying learning and memory.

Along the way, he met a young girl with Angelman syndrome – an experience he says showed him the human side of the disease and “transformed the way” he thought about his research.

Ainsley exhibited the symptoms of the syndrome. Developmentally delayed, she had trouble walking and speaking, and suffered difficult-to-control seizures. But she was also mischievous, with an engaging sense of humor.

“In that way, she was a lot like my own child, but her parents faced day-to-day challenges difficult to comprehend,” Weeber said.

Since then, Weeber has connected with families across the world touched by Angelman syndrome. The motivation to move his team’s scientific discoveries from lab to clinic took on a greater sense of urgency as parents shared their hopes for a cure or a first treatment to make the lives of their children better.

The preclinical work in Weeber’s Byrd Institute laboratory helped fast track minocycline as a drug candidate for one of the first clinical trials for Angelman syndrome. Those trial results are expected to be published later this year.