What Dr. Liwang Cui’s team learns in the laboratory and the field can help curb the spread of this increasingly multidrug-resistant, mosquito-borne disease

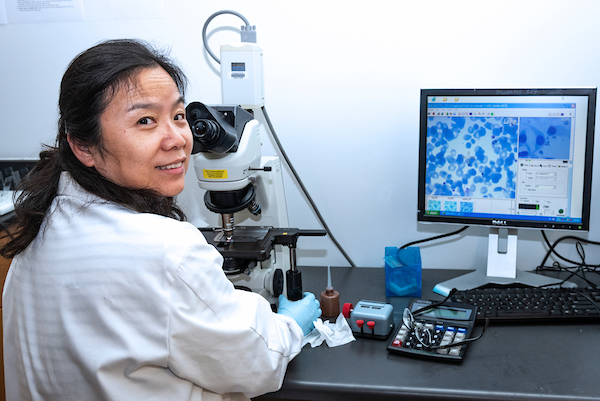

USF Health molecular parasitologist Liwang Cui, PhD, co-leads one of 11 international centers of excellence for malaria research funded by the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

While some of the largest declines in malaria deaths since 2010 have been reported worldwide, the battle continues against the parasite’s resistance to artemisinin-based antimalarial drugs and an emerging threat of mosquito insecticide resistance.

USF Health molecular parasitologist Liwang Cui, PhD, leads a team that is part of an ambitious effort to eliminate malaria from the Greater Mekong subregion (GMS) in Southeast Asia — six countries bound together by the Mekong River — by 2030. Malaria spreads to people through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes (malaria vectors), which inject Plasmodium parasites into the bloodstream. The GMS eradication effort targets both Plasmodium falciparum, the most lethal form of human malaria, and Plasmodium vivax, a less virulent species but the most widespread globally.

Public health officials want to avert a crisis that could arise if the artemisinin-resistant malaria parasites so prevalent in the GMS reach India and then sub-Saharan Africa, where the greatest international burden of malaria lies.

Dr. Cui’s team conducts malaria field studies focused primarily along the border areas of six countries comprising Southeast Asia’s Greater Mekong subregion.

Dr. Cui, the Cohen Professor of Malaria Research in the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Disease and International Medicine, was recruited here last fall from Pennsylvania State University. He was joined by a group of postdoctoral scholars he has mentored and assistant professor Jun Miao, PhD, all from Penn State. USF was recently awarded a new National of Institutes grant to help eliminate malaria in Southeast Asia, with Dr. Cui as the principal investigator.

Collectively these researchers — working both in Dr. Cui’s laboratory at USF and international field study sites — possess diverse expertise, including malaria parasite developmental biology, epidemiology, vector biology, genomics, epigenetics, host-parasite interactions and drug resistance. The Cui laboratory strengthens USF’s growing cadre of medical and public health investigators committed to taking the university’s global infectious diseases research to the next level.

Dr. Cui (center) with team members who joined him at USF from Pennsylvania State University. Their native countries include Cameroon, China, India, Thailand, Uganda and the United States.

And, while malaria is not endemic to the United States, the advances they make have implications closer to home. Travelers who live in areas with no malaria transmission, and therefore acquire no malaria immunity, are among those most susceptible to the severest form of the disease.

“With all vector-borne diseases, our goal is to learn more about the mechanisms of infection, to try to prevent multidrug resistance, and to eradicate the disease before it comes to our doorstep,” Dr. Cui said.

“International travel is so easy now. Today in Florida — tomorrow in Africa, Asia or South America… A few years ago, no one considered that the Zika virus would reach this country, but now the National Institutes of Health is funding Zika research to avoid further outbreaks.”

Postdoctoral scholar Amuza Lucky, PhD, lifts a container of malaria parasites cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen.

The six GMS countries include China, the region’s more economically advanced, which has invested significantly in malaria surveillance, diagnosis, treatment and prevention, particularly in the Yunnan Province counties near its border. Meanwhile hotbeds of the mosquito-borne disease remain in bordering Myanmar, an economically depressed GMS country plagued for decades by ongoing civil conflicts.

“Mosquitoes do not need passports to cross borders, so it is critical to prevent disease introduction and reintroduction at international borders” Dr. Cui said.

Even though China and Thailand have little or almost no malaria now, mosquitoes harboring the parasite on the Myanmar side of the borders, along with highly mobile and displaced ethnic minority populations, could potentially undermine the entire region’s recent progress in combatting malaria, he explained.

After reviving the malaria parasites from cold storage, researchers manipulate the genome of parasites, including those isolated from patients. They use the latest molecular techniques to study gene functions and learn more about drug-resistant malaria.

Dr. Cui is principal co-investigator for the Southeast Asia Malaria Research Center, a network of institutions in the U.S., Thailand, Myanmar and China where internationally recognized investigators conduct coordinated malaria research and education projects.

One of 11 international centers of excellence for malaria research funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the Southeast Asia center (with USF as the lead institution) is currently supported by a six-year, $9.2 million NIAID grant. Its interdisciplinary researchers seek to better define how mobile human populations, parasite drug and insecticide resistance, and mosquito biology contribute to ongoing malaria transmission along international borders, so that more effective control measures can be developed and strategically deployed.

They remain focused on the overarching goal — achieving the World Health Organization’s (WHO) plan to eradicate the life-threatening malaria parasite P. falciparum in the Greater Mekong subregion by 2025, and to make the region malaria free by 2030.

Led by China, the political will to eliminate malaria throughout the region is strong, Dr. Cui said, but the daunting challenges to be overcome require a multipronged approach. Among the challenges:

– Multidrug resistance: The malaria parasite P. falciparum has become increasingly resistant to artemisinin or its derivatives and to several partner antimalarial drugs given in combination with artemisinins. Resistance first reported in 2008 along Cambodia-Thailand border areas has spread to parts of other countries, including Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. This means the drugs take longer to work, and urgency has risen to find new cost-effective compounds to delay drug resistance and halt malaria’s spread.

– Less insecticide effectiveness: Insecticides that reduce the number of mosquitoes have been shown to make a big difference in the incidence of malaria cases. But, growing mosquito resistance to insectides used in long-lasting bed nets and sprayed indoors has become an emerging threat. In Thailand, Dr. Cui said, resistance to pyrethroids, one of only two WHO-approved insecticides to treat bed nets, is now emerging.

– Barriers to care: Malaria distribution is geographically uneven. Vulnerable populations living near borders and remote rural areas lacking access to the latest diagnostics and treatment bear a disproportionate burden of the disease.

– Fake drugs: Falsified and substandard antimalarials present another growing concern, according to WHO. A 2017 survey reported that nearly 28 percent of the antimalarial medicines sold by the private sector in Myanmar were still monotherapy (a single drug) — not the artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) recommended as the first-line treatment for P. falciparum to provide an adequate cure rate. Drug resistance can develop when the concentration of antimalarials in the blood is lacking – at least two drugs (a fast-acting artemisinin and second longer-lasting ingredient) are needed to completely clear malaria parasites, Dr. Cui said.

While the challenges complicate elimination efforts, Dr. Cui’s group and others are fighting back with the latest technology. They employ drones to help map topography and learn more about potential mosquito breeding habitats (ponds, puddles of water) in areas difficult reach by land. They use advanced genetic tools to help track the cross-border movement of malaria parasites and to look for new ways to attack all stages in the complex life cycle of Plasmodium, which can readily mutate to avoid immune system destruction and evolve resistance to drugs.

Dr. Cui is the lead investigator for a $1-million R01 grant from NIAID to identify molecular markers that can help manage P. falciparum malaria’s artemisinin resistance with targeted control measures.

Dr. Cui (green shirt) oversees a team surveying mosquito larvae at a remote field site near the China-Myanmar border, where malaria is endemic.

As he works with his team at the epicenter of drug-resistant malaria in Southeast Asia — whether collecting blood samples used to isolate malaria parasites for genomic sequencing or surveying mosquito larvae sites in rural areas near the China-Myanmar border — Dr. Cui is reminded of the real-world costs of malaria, both in human lives and socioeconomic productivity.

“Malaria is a preventable and treatable,” he said, “so why are we still seeing more than 200 million cases a year worldwide, and nearly half a million, mostly kids, die from this disease?” he said. “When you see the suffering of the people in villages and (refugee) camps it really touches your heart and helps drive your work toward malaria control and elimination.”

USF Preeminence funding helped recruit internationally-recognized malaria researcher Liwang Cui and his team to Tampa.

Dr. Cui received one PhD degree in biology from Moldova Agricultural University (former USSR) and a second in molecular virology from the University of Kentucky; he conducted a postdoctoral fellowship in entomology and molecular parasitology at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, DC. Before coming to USF, he spent 18 years as a professor in Penn State’s Department of Entomology.

Dr. Cui’s malaria research related to parasites, mosquito vectors and human hosts has been continuously funded by the NIH since 2001, and he was awarded two training grants from the NIH Fogarty International Center and one WHO grant for tropical disease research. He has authored more than 240 peer-reviewed publications, including five book chapters. He currently serves as the academic editor of several scientific journals.

Some things you may not know about Dr. Cui:

-

- While he has worked in some very remote areas where malaria remains rampant, Dr. Cui takes plenty of precautions to avoid infection. During his years of field studies in Southeast Asia, he has experienced the effects of civil war and even an earthquake – but he has not contracted malaria.

- Some of his most productive scientific research writing is done late at night and the early hours of the morning, fueled by a pot of freshly brewed tea.

- One of Dr. Cui’s first introductions to Florida wildlife came during an evening jog around the New Tampa subdivision where he lives with wife Rosabel and their two children: Stephen, 3, and Sophia, 9. He stopped short before nearly running over a 6-foot alligator lying in his path – then took a photo with his smartphone from a safe distance.

Photos by Torie Doll, USF Health Communications and Marketing. Field site photos courtesy of Dr. Liwang Cui.