The protein’s role in tau pathology is not well studied, but Alexa Woo seizes the opportunity to be first in discovering something new

USF Health Alzheimer’s disease researcher JungA (Alexa) Woo, PhD, thrives on challenge.

“In terms of science especially, you face many challenges. Your experiments fail, or your hypothesis may not work out the way you expected. It takes a lot of time, effort and a passion for research to publish one paper or get that first grant,” Dr. Woo said.

“I always tell my students, ‘stay positive and be persistent.’ If you stay still, you’re going backwards. So, continue to move forward and try to find something new. Then, your research will contribute to the field and help people who suffer from these terrible diseases.”

Before earning her PhD degree in neuroscience from the University of South Florida in December 2015, Dr. Woo had already managed laboratories for senior scientists, published four papers in Nature-affiliated research journals as a first author, and given oral research presentations at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. She was one of three students across USF to win the 2016 Outstanding Thesis and Dissertation Award for her work on certain molecular pathways that help drive the beta amyloid pathology contributing to Alzheimer’s disease.

Today, Dr. Woo, an assistant professor in the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine’s Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Physiology, runs her own laboratory at the college’s Byrd Alzheimer’s Center. She was recently awarded a five-year, $1.8 million R01 grant from the National Institute on Aging at NIH to study the novel role of proteins known as beta-arrestins, or β-arrestins, in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. She is also the principal investigator of a $221,000 Florida Department of Health Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Grant investigating RanBP9 signaling in tauopathy.

Studying the role of β-arrestins in tauopathy

β-arrestins bind to and modify the function of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), cell surface receptors for hormones, neurotransmitters and other substances that control virtually every cell and organ. GPCRs constitute one of the largest, most diverse protein families in the human genome; in fact, approximately a third to half of all FDA-approved drugs target these ubiquitous receptors.

“Interestingly, all the GPCRs share beta-arrestin as a common regulatory mechanism, particularly in the brain,” Dr. Woo said. “Several groups have found that β-arrestins are increased in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s, and that they promote beta amyloid pathology.”

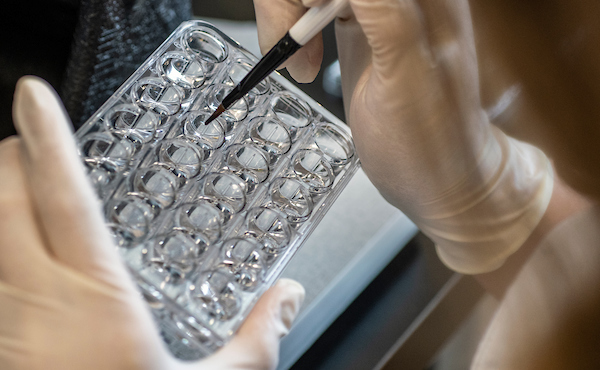

Neuroscientist Alexa Woo, PhD, (seated), an assistant professor of molecular pharmacology and physiology, and her research team in her laboratory at the USF Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Center. Dr. Woo’s research focuses on preventing tau proteins from malfunctioning. When tau malfunctions, it can eventually lead to neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimers.

However, still unstudied is how β-arrestin regulation of GPCR activity may impact the build-up of tau proteins into neurofibrillary tangles that ultimately choke brain cells to death. This represents an important new area of research, Dr. Woo said, because tau tangles more strongly correlate with loss of memory, reasoning and other cognitive abilities than do beta amyloid plaques, the other classic hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

So, Dr. Woo, embraced the challenge of investigating if and how β-arrestins alter the toxic accumulation of tau protein in the brain, known tauopathy. Does this protein linked to GPCRs reduce tau aggregation, or accelerate abnormal tau aggregation?

“Based on my preliminary research, β-arrestins seem to promote tau pathology,” Dr. Woo said. “So, if we can understand how β-arrestins affect neurodegeneration in the brain, we can modify them to mitigate the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.”

In particular, Dr. Woo’s laboratory is trying to determine at what stage in the process of tau aggregation β-arrestins come into play.

Halting the neural wreckage of destabilized microtubules

The researchers also want to figure out how β-arrestins may influence tau’s stabilization of the microtubules that structurally support billions of nerve cells in the brain. Like the railroad tracks needed for trains to move cargo from one destination to another, microtubules transport nutrients, energy-producing mitochondria and other critical materials from the body of the brain cell to distant synapses connecting these components and messages to neighboring cells.

“In Alzheimer’s disease, however, that does not happen,” Dr. Woo said.

Instead, tau clumps together disrupting the communication between nerve cells in the brain, and eventually killing the neurons, she said. Basically, when tau can no longer stabilize these essential rail tracks (microtubules), the destabilized tracks lead to a train wreck – Alzheimer’s disease.

The key is finding new therapies to stop, or delay, Alzheimer’s disease progression in its tracks before it damages the brain beyond repair, Dr. Woo said.

“Once symptoms appear, it means you’ve already been developing Alzheimer’s disease pathology for at least 10 years. So, it’s critically important to find out how we can target pathogenic tau at an early stage – even before nerve cells begin to die.”

At the Byrd Center, basic and translational scientists work under the same roof as physicians conducting clinical research and caring for patients with Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Patients and their caregivers occasionally tour the laboratories where faculty and students update them on USF Health discoveries in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.

“When you meet and talk to people affected by this disease, it really motivates you to learn from what’s already been done and to continue moving ahead with your research,” Dr. Woo said. “I’m hopeful that we will be able to find new treatments and, ultimately, a cure.”

“Put your head down and focus on your research”

Dr. Woo received her master’s degree in biomedical science from Seoul National University in South Korea before coming to USF to pursue a PhD focused on neuroscience at the USF Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Center.

She became fascinated by the relationship between GPCRs and β-arrestins while working as a postdoctoral scholar in the laboratory of Stephen Liggett, MD, professor of internal medicine and molecular pharmacology and physiology, vice dean for research for the Morsani College of Medicine, and USF Health vice president for research. Dr. Liggett studies the genetics, molecular biology, structure and function of GPCRs and his research has provided key insights into GPCR activation, identifying many of the regulatory steps that coordinate multiple signals sent and received by all cells in the body.

“Dr. Liggett always challenged me to be my best as a scientist,” Dr. Woo said. “The first thing he said to me was ‘put your head down and focus on your research. That’s the most important thing.’”

So, she persisted — seizing every opportunity to improve her research along the way.

Two years ago Dr. Woo was recruited by MCOM as an assistant professor. Now, with her own laboratory at the Byrd Center, this junior faculty member mentors new emerging scientists, encouraging (and challenging) them to excel.

The red-orange image on the computer monitor next to Dr. Woo depicts movement of mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell.

Some things you may not know about Dr. Woo:

- She was born and reared in Andong, South Korea, famous for its history as the Korean home of Confucian learning, which has produced many leading scholars.

- Dr. Woo originally wanted to become a South Korean military officer like her uncle. “So instead of managing a military base, now I manage my lab. Although some students may think I manage the lab like a military officer,” she said with a laugh.

- She is married to David Kang, PhD, professor of molecular medicine and director of basic research for the USF Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute.

- Since age 6, she has played classical piano, and still enjoys playing piano as a hobby. Her favorite composer is Chopin.

-Video and photos by Allison Long, USF Health Communications and Marketing